Justification and Belief in Epistemology

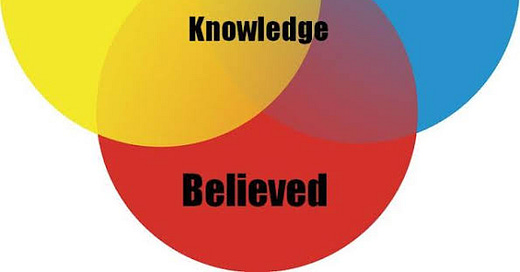

In epistemology, the branch of philosophy that deals with knowledge, the concepts of justification and belief play central roles. To understand what it means to “know” something, philosophers have long debated what makes a belief justified — and whether justification is even necessary for knowledge.

1. What is Belief?

A belief is an attitude a person holds toward a proposition or statement — essentially, believing that something is true. For instance, if you believe that the sun will rise tomorrow, you hold that proposition to be true. Beliefs can be true or false, and they exist regardless of whether one has strong evidence for them.

However, mere belief is not sufficient for knowledge. If someone makes a lucky guess and happens to be right, we might say they believe the truth — but we would hesitate to call it knowledge.

2. The Role of Justification

Justification refers to the reasons or evidence that support a belief. In traditional epistemology, knowledge is often defined as “justified true belief” (JTB) — a belief that is true and for which the believer has good reasons.

For example, if you believe it will rain because you saw the forecast, and it does rain, your belief is justified by the evidence (the weather report). This makes your belief more than a lucky guess — it’s rational.

But justification is a complex concept. Questions arise like:

What counts as good justification?

Is justification internal (based on what’s in your mind) or external (based on factors outside your awareness)?

Can someone be justified and still be wrong?

3. Internalism vs. Externalism

There are two major perspectives in epistemology regarding justification:

Internalism holds that justification depends on factors accessible to the thinker’s conscious awareness — like reasons, evidence, or experiences.

Externalism argues that justification can depend on factors outside the thinker’s awareness — such as the reliability of the belief-forming process (e.g., trusting your vision if it’s usually reliable).

4. The Gettier Problem

In 1963, philosopher Edmund Gettier challenged the traditional “justified true belief” model by presenting cases where someone has a belief that is justified and true, but still seems like they don’t have knowledge. For example, someone might believe that their friend owns a Ford because they saw him driving one yesterday. Unbeknownst to them, the friend sold the car that night — but coincidentally, he rented another Ford today. The belief is true and justified — but it’s true by accident.

Gettier’s cases sparked a wave of new theories about what more might be needed for real knowledge — such as “no false lemmas,” “reliabilism,” or “truth tracking.”

5. Why It Matters

Understanding justification and belief is crucial for evaluating how we form knowledge in science, religion, ethics, and everyday life. It helps us differentiate between informed belief, opinion, superstition, and reliable knowledge. In an age of misinformation, being able to assess whether a belief is justified is more important than ever.

If truth is what we are after, and knowledge is based on a collection of "facts" learned from others or by personal experience, it is inconclusive. Truth never changes, science constantly questions and tests what are accepted as facts to discover the truth (completely opposite to saying "I am the science" based on knowledge of facts). Teaching people to believe a collection of knowledge makes a person "educated" rather than teaching them how to use their brains to think critically and be curious is a fraud. "It is a miracle that curiosity survives a formal education." - Albert Einstein

For anyone interested in epistemology, I suggest looking at the Pramanas. The Samkhya, Yoga, Purva Mimamsa, and Uttara Mimamsa schools have a lot to say, as well as the Buddhist and Jain schools who inherited some of the concepts.