What love is and how it affects ethics and politics? For philosophers, the question “what is love?” brings up many issues. Love is an abstract noun, so for some people, it is just a word that doesn’t refer to anything real or clear. For others, love deeply changes who we are and how we see the world once we experience it. Some people try to study and explain love, while others think it cannot be fully explained.

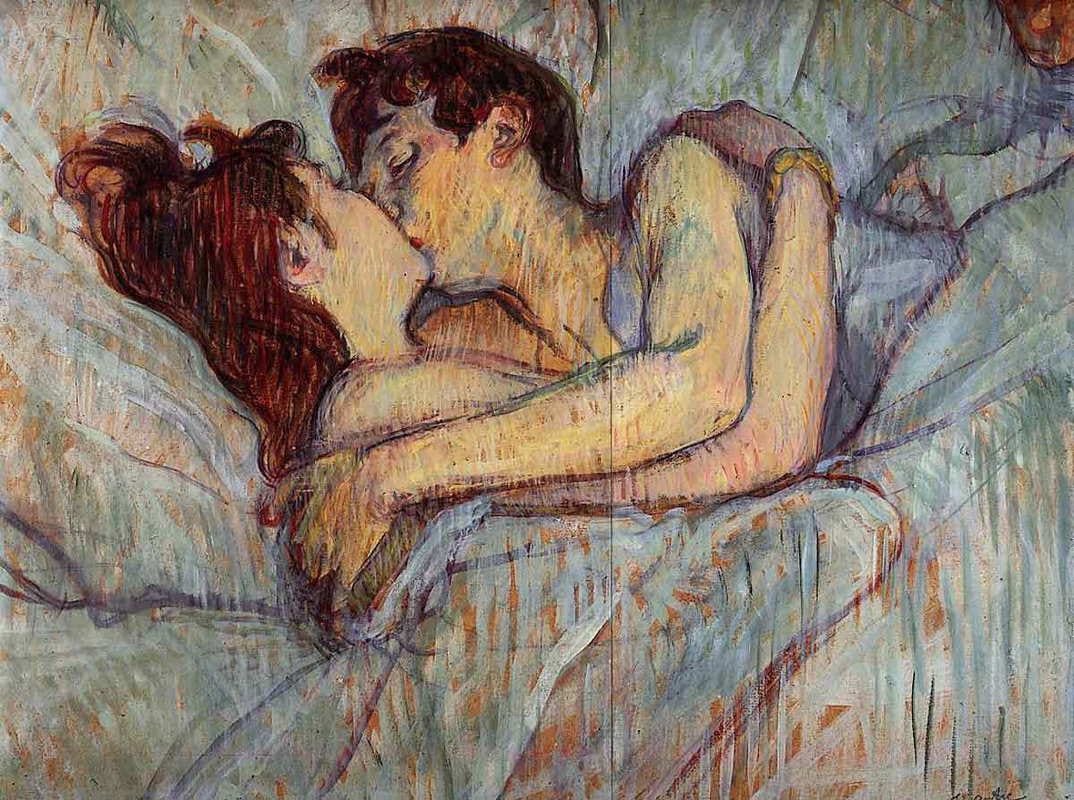

Still, it is clear that love is a big and important part of our cultures. We hear about it in songs, movies, and books—sometimes in a funny way, sometimes in a serious way. Love is often part of growing up and is especially strong in youth. In philosophy, love has been an important topic since the time of the Ancient Greeks. Some theories say love is just a physical feeling—an animal or genetic urge that controls how we act. Other theories say love is a deep spiritual experience that can even connect us with the divine.

In Western philosophy, Plato’s Symposium is the starting point. It gives a powerful and popular idea that love grows in stages. It begins with physical desire or lust, then becomes more about the mind, and finally reaches a higher form of love that goes beyond physical attraction and shared feelings. Since then, some have supported or rejected Plato’s idea of love. There are also many other theories, including one from Plato’s student Aristotle. His more everyday idea of love described it as “two bodies and one soul.”

The philosophy of love covers many areas such as knowledge, existence, religion, human nature, politics, and ethics. Ideas about love often link to main ideas in philosophy and are also looked at alongside ideas about sex, gender, the body, and human intention. The goal of the philosophy of love is to clearly explain the key issues, using ideas about human nature, desire, and ethics.

1. The Nature of Love: Eros, Philia, and Agape

Philosophers start thinking about love by asking what its nature is. This assumes love has a “nature,” but some people argue that love is not logical—it cannot be explained using reason. These critics say love is just strong emotion that does not follow rules. Some languages, like Papuan, don’t even have a word for love, which makes it hard to study it philosophically. In English, the word “love” comes from an old word meaning “desire,” but its meaning is very broad and unclear. To help with this, we look at three Greek words for love: eros, philia, and agape.

Eros

Eros comes from a Greek word meaning a deep desire, often sexual. It’s where we get the word “erotic.” But in Plato’s writings, eros is more than just sexual desire—it is a strong wish to experience perfect beauty. The beauty we see in a person reminds us of a higher, ideal beauty that exists in a spiritual world. For Plato, love for beauty on earth can’t fully satisfy us; we should try to go beyond the physical to understand beauty itself.

Plato’s idea means that the beauty we love in people, ideas, or art is really a reflection of a perfect kind of beauty. We don’t love the person for who they are, but for the ideal beauty they represent. In Plato’s view, love doesn’t need to be returned. The focus is on the beauty itself, not on shared feelings or companionship.

Many philosophers agree with Plato that this kind of love is higher than physical desire. Physical desire is something animals feel too, so it’s seen as a lower form. Real love should come from thinking and understanding, not just feelings. True love, then, is about seeing the beauty of the soul or idea, not just liking someone’s looks or actions.

Philia

Philia is a different kind of love. It means fondness and appreciation. In Greek, it includes friendship, family love, and loyalty to one’s community or profession. According to Aristotle, philia can happen for three reasons:

Because someone is useful to you (like a business partner).

Because you enjoy their company (they’re fun or pleasant).

Because you value them for who they are (their character).

Aristotle says the best kind of friendship is based on shared values, fairness, and respect. Good people make good friends. People who are mean, unfair, or difficult cannot create real philia. The best friendships are between people who are similar in virtue and character. These are rare and involve deep respect and admiration.

Friendships that are based only on fun or usefulness are less strong. For example, a business friendship ends when the work ends. Friendships based on fun end when the fun stops.

Aristotle also says you must love yourself first to love others well. But this self-love isn’t selfish—it means loving the good and noble parts of yourself. Then you can share thoughtful and deep friendships with others. The best friendships are between people who share ideas and live a good life together.

In some cases, love can be one-sided, like the love of a parent for a child. Aristotle believes love should be balanced, but not necessarily equal. The better person can be loved more, and not have to love back in the same way.

Agape

Agape is a kind of love that comes from God. It is both God’s love for people and people’s love for God. But it also includes a universal love—loving all people. This kind of love combines parts of both eros (deep passion) and philia (fondness and loyalty). Agape is about loving without needing love in return.

In the Bible, this love is expressed in two commands:

“Love God with all your heart, soul, and strength.”

“Love your neighbor as yourself.”

This kind of love is similar to Plato’s idea of loving perfect beauty—it is passionate, pure, and goes beyond everyday worries. Christian thinkers like St. Augustine and Aquinas connected these ideas. Augustine saw this love as divine and spiritual. Aquinas thought God is the most rational being, and so the most deserving of our love.

The idea of “loving your neighbor” is challenging. Some philosophers argue it means loving everyone equally, even enemies. But others, like Aristotle, say real love can’t be shared equally with everyone. You can’t be best friends or deeply in love with many people at the same time. Still, Christian thinkers believe we must try to love everyone, even if they don’t deserve it. This shows moral strength and forgiveness.

Some argue that even if you love someone, you can still criticize their actions. You can love someone’s soul, even if their behavior is bad. Christian pacifists believe in showing love even to enemies, hoping they will one day change.

Agape is different from Aristotle’s view. It says we should love all people equally, while Aristotle believed in loving those who deserve it more. Modern thinkers like Kierkegaard agree with the Christian idea of equal love. Others argue that true love requires closeness and understanding, which usually comes from loving a few people deeply.

2. The Nature of Love: Further Conceptual Considerations

Philosophers ask whether love, presuming it has a "nature," can be meaningfully described or understood through language. Some argue love is an irreducible, private emotional state—possibly beyond rational or linguistic analysis. Emotivists and phenomenologists like Scheler emphasize love as non-cognitive, suggesting it cannot be dissected logically, and is instead passively experienced, as though value emerges from the beloved without effort by the lover.

Others believe love should be examined if people make moral or behavioral claims like "she should show more love." Philosophical inquiry then asks whether love is just behavioral patterns, emotions, or the pursuit of values. Even if love has a nature, it may be inaccessible to full human understanding, like Plato's Forms—ideal concepts of which we only perceive shadows.

Plato's influence leads to two interpretations:

Love is knowable only to the experienced or philosophically trained.

Love, especially romantic or idealized love, transcends base desires and is understood only by the few, such as philosophers, poets, or mystics. This creates a hierarchical view—where true love is separated from mere physical desire.

3. The Nature of Love: Romantic Love

Romantic love, distinct from mere physical attraction, has deep philosophical and historical roots. It originates in Plato’s idea that love is a desire for ideal beauty, ultimately leading to the love of wisdom (philosophy). In this sense, romantic love is metaphysically and ethically superior to physical desire.

Medieval notions of courtly love (fine amour) reflected this Platonic tradition, with knights honoring ladies in noble, often unconsummated relationships. Such love was expressed through chivalric action, not physical possession—a contrast to the sensual and strategic love described by Ovid in Ars Amatoria.

Modern romantic love leans toward Aristotle’s idea of a special union based on virtue and shared values: “one soul in two bodies.” It is viewed as a higher form of love, encompassing emotional, ethical, and philosophical dimensions—not just physical or behavioral ones.

4. The Nature of Love: Physical, Emotional, Spiritual

This section explores competing theories of love—whether it is primarily physical, emotional, or spiritual:

Physicalist views (e.g., geneticists, determinists) reduce love to biological or chemical impulses—such as sexual attraction or reproductive instinct. However, these theories struggle to explain non-reproductive or ideational forms of love like friendship (philia) or unconditional love (agape).

Behaviorists define love through observable actions and preferences (e.g., acts of care, preference toward someone). They argue love is quantifiable by behavior, but critics note people can act lovingly without feeling love, and internal states may not align with external behavior.

Radical behaviorists like Skinner claim mental states can still be studied via the conditions that produce them, viewing love as a strong positive reaction to certain environmental triggers.

Expressionist theories agree love is behaviorally expressed, but emphasize that it is ultimately rooted in an internal emotional state, not just physical stimulus-response.

Spiritualist perspectives see love as a recognition or union of souls, transcending physical or behavioral explanations.

Aesthetic theories hold that love is a felt emotional experience, best expressed through metaphor, music, or poetry, rather than through rational language or analysis.

5. Love: Ethics and Politics

Love also raises ethical and political questions:

Ethically, questions arise about the moral appropriateness of love:

Is it right to love oneself or objects?

Is universal love a moral duty, or is partiality (loving some more than others) acceptable?

Should love transcend physical desire?

These debates intersect with sexual ethics, touching on issues of appropriate sexual behavior, reproduction, and inclusivity regarding heterosexual and homosexual relationships.

Politically, love can be viewed as a social construct serving power structures:

Some feminist and Marxist thinkers argue love functions like religion in Marxist theory—an opiate used to disempower women and uphold patriarchal norms.

Under this view, traditional ideas of love (e.g., courtship, romantic obligation) reflect broader social and linguistic controls over individuals.

The substack post concludes by noting that love, as a philosophical concept, touches on many domains: human nature, mind, ethics, language, and politics—revealing its complexity and deep entwinement with broader philosophical questions.

Thanks for reading keep supporting human philosophy.

Recommended posts you might read:

How Do I Know If I’m in a Relationship with a Narcissist? Signs, Symptoms, and What to Do

How to Improve Your Emotional Intelligence for Better Relationships and Success

How to Spot Fake Nice People: Key Signs and Red Flags to Watch For

The Dark Side of Success: How Ambition Can Lead to Moral Compromise

The Narcissistic Mask: How Charisma Can Hide a Dark Personality

Read an interesting poem about love!

Wonderfully explained