Positivism: Is it Dead?

The philosophy of science was shaped by positivism from the 19th century to the 20th century. What caused its fall from grace?

While positivism was the most defining philosophy of science in the 20th century, it is now considered dead. Today, it is often used more as an oppositional term, a caricature or a strawman, easily dismissed and used to prop up newer ideas. Despite the criticism, especially of logical positivism, many of its core ideas still influence modern philosophy of science and have helped shape fields like logic and the humanities. This leads to an important question: Was its obituary written too hastily?

Positivism: Towards Modern Science

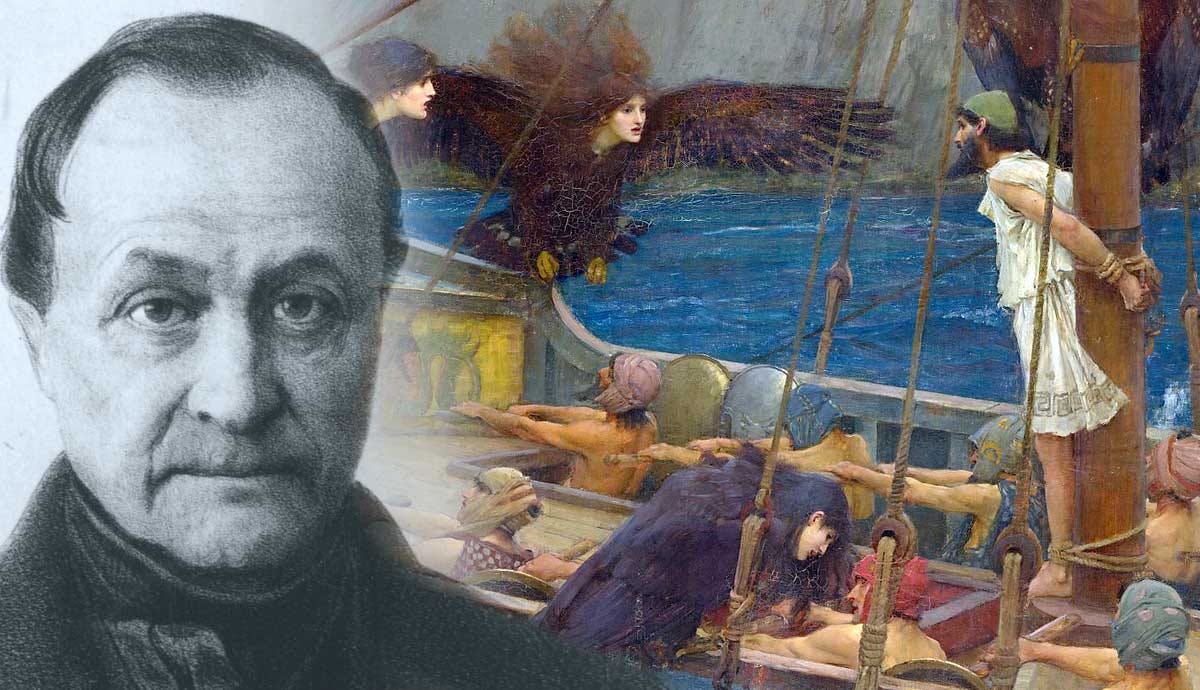

Positivism was originally introduced by Auguste Comte, who was heavily influenced by his teacher Saint Simon. It marked an important first step toward a modern philosophy of science. However, at the time, positivism was more of a movement aimed at improving society.

Comte’s ideas are reflected in one of his sayings: “Love as a principle and order as the basis; Progress as the goal” (Comte in Système de politique positive, 1841–45, p. 19). He wanted to create a rational method of thought by taking a historical perspective. He also aimed to make science completely secular, moving it away from religious influence.

Comte believed that scientific (or "positive") knowledge was the final stage in the development of a society’s understanding, following the theological and metaphysical stages. For this reason, he wanted to move beyond metaphysical knowledge, which he saw as a leftover from Enlightenment rationalism that hindered progress.

He also proposed a hierarchy of the sciences. In this hierarchy, more general and less complex sciences like physics are at the top, while more complex and dependent ones like sociology are at the bottom. This structure implies that the higher sciences are more determined.

Hume’s Influence on the Development of Positivism

The positivist philosophy was deeply influenced by David Hume’s empiricism and scientific anti realism. According to this view, knowledge about facts could only come from observable data or logical proof. Theoretical entities and laws like electrons and gravity that are not directly observable were treated as tools for prediction.

This view naturally leads to an anti metaphysical stance. As Hume famously said:

“If we take in our hand any volume; of divinity or school metaphysics, for instance; let us ask, Does it contain any abstract reasoning concerning quantity or number? No. Does it contain any experimental reasoning concerning matter of fact and existence? No. Commit it then to the flames: for it can contain nothing but sophistry and illusion.”

Logical Positivism: Language and Logic

The next major development in the philosophy of science was logical positivism, also known as logical empiricism. Its advocates preferred the latter name to distance themselves from the baggage of earlier positivism. Still, their ideas were a direct continuation of that tradition, building on the work of later positivists like Mach and Avenarius.

Logical positivism consisted mainly of two groups: the Vienna Circle, led by Rudolf Carnap, Otto Neurath, Hans Hahn, and Moritz Schlick, and the Berlin Society, led by Hans Reichenbach.

Like positivism, logical positivism was more a movement than a fixed doctrine. It shared the goal of societal improvement. One of its major aims was to unify the sciences, which it hoped to achieve through a unified scientific language. The movement also sought to eliminate unverifiable claims, even those appearing in science itself.

Because of this continuity, people often confuse logical positivism with the earlier positivist movement.

Unifying Science Through Language

Logical positivism took a new approach by using the philosophy of language, meaning, and logic.

They saw logic and mathematics as potential universal languages for science. By expressing theories and laws in these precise languages, they hoped to eliminate ambiguity and ensure rigor in both science and philosophy.

Wittgenstein’s Tractatus and Bertrand Russell’s work in logic inspired this vision. Their ideas suggested that language’s structure reflects the logical structure of the world. This made it possible to link mathematical truths to the real world through logic, rather than metaphysics, an idea attractive to empiricists.

Building on Hume's analytic synthetic distinction, logical positivists refined it. They believed the truth of statements could be known either through meaning and logical structure or through empirical observation.

They wanted logic to make scientific and philosophical language clear, precise, and universal.

A major part of this effort was the verification principle, first proposed by Wittgenstein. According to this principle, a statement is scientifically meaningful only if it can be verified analytically or through observation. This ruled out metaphysical, ethical, and aesthetic statements as scientifically meaningless.

However, "meaningless" in this context meant lacking truth value, not lacking personal or philosophical importance.

Questioning the Logic of Logical Positivism

Though logical positivism began with bold goals, it soon faced serious problems.

Gödel’s incompleteness theorems and Tarski’s undefinability theorem revealed that formal languages, even logical and mathematical ones, have limits. These results undermined the idea of a complete and consistent language for science.

The verification principle itself was problematic. The verifiability paradox showed that the principle couldn’t verify itself, making it self contradictory.

Willard Van Orman Quine challenged the foundation of logical positivism in Two Dogmas of Empiricism. He questioned the analytic synthetic distinction and even the need for analyticity. He proposed that our beliefs form a holistic web, with no strict line between logic and observation. He also rejected the idea that meaning can be reduced to experience.

These criticisms weakened logical positivism and led to its decline. Its goals were ambitious, but the obstacles were too great.

Carnap’s Response

Despite the collapse of logical positivism as a unified movement, its ideas evolved.

Rudolf Carnap, a key figure, tried to overcome the problems. In response to Gödel’s findings, he shifted focus from syntax to semantics, emphasizing meaning and truth rather than just form.

He introduced the Principle of Tolerance, which allowed for multiple scientific languages, each valid as long as it followed scientific methods. This was a more flexible view than trying to enforce one universal language.

Carnap also moved from strict verificationism to confirmationism, accepting that scientific knowledge often relies on probabilistic evidence rather than absolute proof. He also acknowledged the complexity of science, moving away from defining all concepts through observation.

Though Carnap stayed committed to empiricism, he adapted logical positivism to new challenges. His work shows that the movement was never rigid, it was open to revision and growth.

Postpositivism: Incorporating Criticisms

Carnap’s developments were part of a broader shift to postpositivism. This new phase built on the criticisms of logical positivism while keeping many of its core goals.

Postpositivism recognized the limits of rationality and empiricism. It acknowledged that science is influenced by subjectivity and fallibility.

Thinkers like Thomas Kuhn played a major role in this shift. His idea of theory laden observation showed that what we observe depends on the theories we believe. This challenged the positivist idea of purely objective observation and a universal scientific language.

Postpositivism embraced a pluralistic view of science. It accepted the idea of approximate truth and allowed for the reality of unobservable entities, moving closer to scientific realism by relaxing strict empirical rules.

Death or Death of a Caricature?

John Passmore wrote: “Logical positivism, then, is dead, or as dead as a philosophical movement ever becomes” (Passmore, 1967, p. 57). As a movement, it did fade. But many of its ideas lived on, something often overlooked.

Unfortunately, logical positivism is now often seen as a caricature of philosophy, reduced to a form of scientism that dismisses anything outside empirical science. Yet the movement never claimed that metaphysics, ethics, or aesthetics were useless, just that they lacked scientific truth value.

Another common misrepresentation is that positivists rejected the existence of unobservable entities. In reality, they often accepted such entities as useful tools for prediction, a view close to modern scientific anti realism.

A. J. Ayer’s Influence

Much of the misunderstanding of logical positivism comes from A. J. Ayer’s writings about the Vienna Circle. He provided the first major English language account of the movement, which was more accessible than works by figures like Carnap.

Ayer emphasized the verifiability criterion, giving the impression that it defined the movement. But this was not central to thinkers like Carnap, who had a more nuanced approach.

In the end, what declined was not just positivism, but the overly simplistic idea of science as a purely rational and empirical endeavor, along with the belief that philosophy of language could provide a final answer to truth.

Still, the spirit of positivism continues in naturalism and modern philosophy of science.

must share your thoughts in comments.

Thanks for reading. Please do support the Human Philosophy by buy me a coffee.

Read more about Human Psychology and thank me later.

10 Mind-Blowing Facts About Social Psychology You Need to Know

10 Surprising Ways Stress Affects Your Mind and Body—and How to Fight Back!

The Dark Side of Success: How Ambition Can Lead to Moral Compromise

The Narcissistic Mask: How Charisma Can Hide a Dark Personality

The Power of Habits: How to Build Positive Routines and Break Bad Ones

The Psychology of Envy: How Jealousy Shapes Our Thoughts and Actions

Trump has brought back positivism in spades....

Tim